Portfolio: How Notetaking Becomes Knowledge

First in a series on Portfolio: a comprehensive system for notetaking in Obsidian.

If you’ve followed my writing about notetaking over the past few years, the title of this post — Portfolio: How Notetaking Becomes Knowledge — may be familiar. In May 2024, I published Folio: How Notetaking Becomes Knowledge, in which I laid out some of the principles of a system I’d developed over the preceding few years, built on the underlying Obsidian platform, which I called Folio. Today, I am introducing what could have been called Folio 2.0, but the changes I’ve made are significant enough to warrant a new name: Portfolio. (Also, the whole 2.0 thing is kind of played out, don’t you think?)

I won’t take the course of recapping what Folio was and all the changes I’ve made. However, Portfolio is the outgrowth of actively pursuing the goals of Folio over the course of an additional year in the trenches of the daily use of Obsidian as a notetaking, work management, and knowledge management platform.

The Goal for Portfolio

People have used notetaking for centuries to accumulate insights, ideas, quotes, and drawings with the end goal of capturing a body of knowledge in search of consilience: that is, the aspiration that cross-pollination of various — perhaps initially unrelated notes and clippings — can lead to spontaneous and unforeseen breakthroughs. Breakthroughs in both personal understanding and perhaps in the advancement of ongoing explorations in science, art, and social relations, individually and communally.

The rise of digital notetaking systems has amplified these aspirations, and provide means to push notetaking to new levels of sophistication and greater depth of understanding for users. However, the effective use of notetaking systems like Obsidian, Notion, Roam Research and others requires more than reading the manual and jumping in.

Portfolio is a system to accomplish that aspiration in Obsidian.

I chose the name based on the notion of a physical portfolio, ‘a hinged cover or flexible case for carrying loose papers, pictures, or pamphlets’, but in this instance the ‘portfolio’ is metaphorical, since the Obsidian platform does not really involve printed materials, but rather a collection of notes captured in a digital file system.

Portfolio is a consolidation of many aspects of Obsidian's notetaking capabilities, starting with the primitives of its form of Markdown, as well as more complex and sophisticated functionality from core and community plugins. Portfolio is also a set of principles and practices intended to support the development of a deep base of knowledge for whatever domains the user wishes to explore, and to assist the user in generating new insights, personal understanding of these domains, and perhaps the creation of new materials advancing communal understanding as well.

But first and foremost, Portfolio is a system organized around personal management of information, and the management of that information for purposes of work and knowledge management. Said in a simpler way, Portfolio is intended to help users keep track of things, to be able to find them, and to provide the infrastructure to harness that information — whether gathered from the outside, like clipped articles, or notes created solely within Obsidian — to accomplish whatever goals.

My goals for Obsidian, since I am a writer, consultant, and analyst, often revolve around reading and writing, so many of the examples are derived from use cases close to those interests.

Setting Context: Not an Obsidian Tutorial

This post presupposes the reader will have a basic understanding of how Obsidian works: this is in no way a tutorial to the Obsidian platform.

Also, much of what it proposed here might be applicable to other platforms, like Notion, or Roam, but I have not undertaken experiments to see how that might play out. So, in general, Portfolio is pretty specific to Obsidian, and relies directly on features specific to Obsidian, such as transclusion, Obsidian’s versions of Markdown and search, and wikilinks.

I intend to take the reader through a use case central to my everyday use that introduces some elements of Portfolio, a taste of things to come in this series. In the coming weeks, I will be writing others in this series on topics like these:

The Portfolio knowledge base (based on file references (or taxa), not tags or the Dataview system); and how that enables networked knowledge.

The central role of interstitial journaling rather than dashboards (daily, weekly, monthly notes);

Portfolio work management (multistate tasks and task search), the use of the Projects plugin, and its model of notes, states, and views, and ‘taxa-based’ search.

Annotations (sidenotes, footnotes, highlights, ‘precis’);

How Portfolio’s parts all work together, and other considerations, like events, cadence, notifications, and the pros and cons of plugins.

A Core Use Case: Clipping and Annotating a Web Article

I read a lot, and I mean ‘close reading’. I heavily annotate materials, adding footnotes, highlighting text, inserting links to other materials. My intention is generally to use such information in my research and writing, and I try to associate imported materials with ongoing or new projects. Note that all of these purposes rely on importing the materials: I can’t simply rely on a hypertext link to, for example, a post on Paul Krugman’s Substack, or an article on the New York Times. I need to manipulate and augment the starting materials and enmesh it in an information network on Obsidian.

I rely these days on the official Obsidian Web Clipper on Chrome, but in the past I used other less sophisticated tools.

Here’s an example, a recent post by Paul Krugman, The Economics of Left-Behind Regions. I glance at the article and realize that it fits with my ongoing research on ‘left-behind’ regions in the Western world. I decide to clip it into Obsidian:

Hovering is the pop-up for the Web Clipper on Chrome. Based on its templates (see The Official Obsidian Web Clipper Plugin), a lot of key information is pulled into the various elements of the to-be note. I’ll describe the various bits in a minute, but I have crated the Wen Clipper template specifically to work with Portfolio. The template is past the paywall at the bottom.

Once imported to my ‘00 journal folder’ in Obsidian (directed by settings in the Web Clipper template), the new note is ready for my manipulation. Here’s what the top of the note looks like after I’ve read and annotated the note:

At the top of the note are various note properties, followed by a region of the note I call the ‘precis’ which runs from the H2 headline of the clipped article (with link back to the original), various notes I’ve taken or quotes I’ve pulled from the imported material, and ending with an H2 heading, ‘## body’, which acts as the endpoint for references to the ‘precis’ region of the note. Note that the remainder of the Krugman piece starts with ‘A few days ago the New York Times’.

Here’s the source version of the top of the note, which helps to understand what’s going on:

One core concept in Portfolio is the use of taxa — notes that represent elements in a taxonomy. In the top-most heading, there is a wikilink reference to a file called ‘@Paul Krugman’:

[[@Paul Krugman|Paul Krugman]]

In the Portfolio knowledge base, I have created a folder called ‘people’, and notes created with ‘@’ as their first character are automatically moved there (using the ‘Auto Note Mover’ plugin). The section with the bar — ‘| Paul Krugman’ — denotes an alias without the ‘@’sign.

In edit or reading mode, clicking on that reference will open that file, and with the help of the ‘Rich Foot’ plugin, we can see all the notes in my vault that refer to ‘@Paul Krugman’:

Trust me, there are hundreds of people being similarly tracked in my Portfolio.

Returning to the previous screenshot, you can see other sorts of taxa in the precis section, in particular this task:

- [?] [[•stoweboyd.io]] [[+economics]] [[~peripheral America]]: [[2025-03-02 The Economics of Left-Behind Regions - Paul Krugman]]

The question mark in ‘- [?]’ denotes a ‘maybe interesting’ task using the extended task states supported by various Obsidian themes: in my case, Minimal. Then, left to right, three additional taxa references:

a ‘project’ denoted by leading ‘•’, ‘•stoweboyd.io’;

a ‘concept’ denoted by ‘+’, ‘+economics’; and

a ‘place’ denoted by ‘~’, ‘~peripheral America’.

And at the end of the task, a wikilink back to the note itself, ‘[[2025-03-02 The Economics of Left-Behind Regions - Paul Krugman]]’.

Each of these taxa — and others — have their corresponding subfolders in the Portfolio knowledge base. Note that the next installment in this series will focus on taxa — their use and purpose — is great depth. For now, suffice it to say they serve to annotate the task with information so that

the task can be found by taxa-based search, and

aggregated with other tasks and notes.

So at a later point, I might want to find all ‘@Paul Krugman’ posts that touch on ‘+peripheral America’, ‘~East Germany`, and the ‘+far-right’, or any permutations of those taxa. These annotations make that possible.

I have not touched on other annotations of this and other notes. I will save that for another installment in the series. However, the liberal use of many taxa leads to a Rich Foot for that note like this:

Linking That Use Case To The World

Clipping a note into my Obsidian vault, ends with at least one connection to other notes. I rely heavily on Obsidian ‘Daily Notes’. Each day I create a Daily Note of the form ‘2025-03-02’, and as I undertake various actions — like capturing ideas, or clipping/annotating web pages like the Krugman post — I add entries to the Daily Note, like this:

A heading timestamp is the top of the entry, and then the entry, which in this case is only the transclusion of the ‘precis’ from the imported Paul Krugman note. That transclusion source is this:

Yes, that is complex, but I never hand construct it: I created in the Paul Krugman note after I finished annotating it, by creating a 'copy heading embed’ through a right-click menu supported by the ‘copy block link’ plugin.

I then paste that link to the note entry.

Conclusions

I’ve thrown a lot at you in this one use case, but I tried to approach it on a step-by-step technique, rather than arguing grand principles. Trust me, those principles will surface in the coming series, which will include these elements of Portfolio:

The Portfolio knowledge base (based on file references (or taxa), not tags or the Dataview system); and how that enables networked knowledge.

The central role of interstitial journaling rather than dashboards (daily, weekly, monthly notes);

Portfolio work management (multistate tasks and task search), the use of the ‘Projects’ plugin, and its model of notes, states, and views, and ‘taxa-based’ search.

Annotations (sidenotes, footnotes, highlights, ‘precis’);

How Portfolio’s parts all work together, and other considerations, like events, cadence, notifications, and the pros and cons of plugins. And how Portfolio is likely to change based on Osodian’s Roadmap.

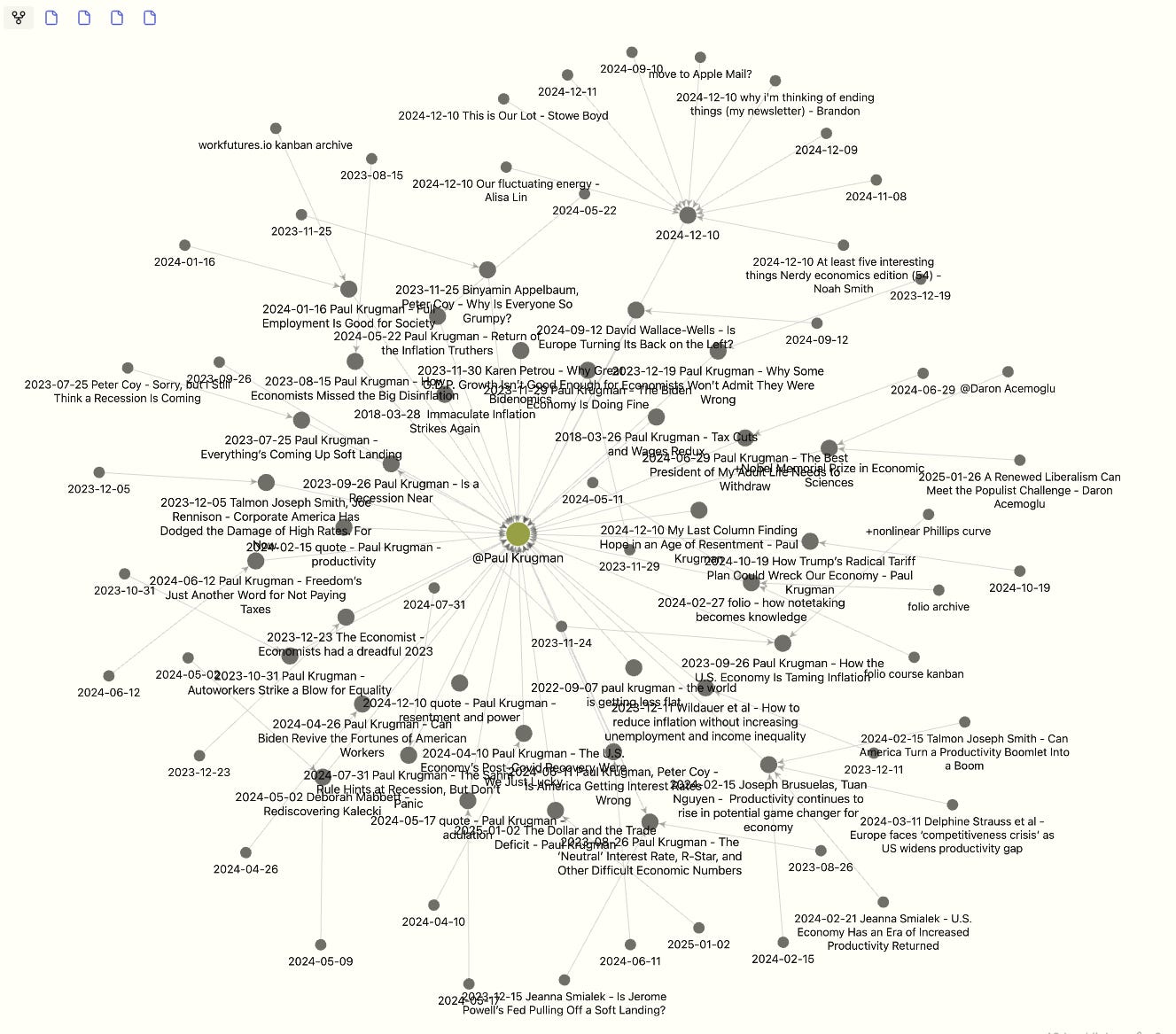

The accumulation of tiny actions — creating taxa, embedding links, using plugins — leads to a rich tableaux of notes and connections, which leads to a graph like this, centered on Paul Krugman:

The full graph is so large and dense it isn’t profitable to look at it in full: only smaller, shallower graphs are useful. You’ll see how useful they can be.

The Web Clipper Template is on the other side of this paywall:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Workings to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.